Returning to the Mud: What Resilience Feels Like at Ground Level

February 16, 2026 | Ksar el Kebir, Morocco

I. The Checkpoint and the Roman Road

I arrived at 4:30 PM. The sun was low, casting that golden Mediterranean light—the kind painters chase and photographers filter. The sky was a deep, clean blue, as if it had been washed by the same rains that flooded us.

At the entrance to the city, there were barricades. Only one road was open: the National Route 1. The road I call “the Roman road” — the ancient route that once connected Volubilis to Oppidum Novum (what we now call Ksar el Kebir) and continued all the way to Lixus, where the Loukkos meets the Atlantic.

My car has a local license plate: A42. Ksar el Kebir. The gendarme at the checkpoint glanced at it, then waved me through without a word. No documents needed. The plate was enough. The city recognized its own.

Inside, the city was calm. Too calm. The air was pure—no pollution, no dust. After days without movement, without the usual agitation, the visibility was startling. Every detail of the buildings, every crack in the walls, stood out as if drawn in charcoal.

And the smell: a complex layer of humidity, rotting vegetation, distant bleach, and something else—more oxygen. As if the flood had scrubbed the air clean even as it left its signature in odor.

II. The House on the Hill

My neighborhood sits on a small hill, like an island above the rest of the city. The waters never reached it. Everything was intact—the street, the door, the walls. It felt as though I had left only yesterday, not twelve days ago.

I opened the door.

The first thing that hit me was the fridge. In my haste to evacuate, I hadn’t emptied it. Fruits, vegetables—all rotten. Their smell mixed with mold and humidity, a thick welcome that filled every room.

I climbed to the terrace. From there, the city spread beneath me like a map. My neighborhood was indeed an island—a patch of dry land surrounded by brown traces where the water had been. Mud covered everything beyond our hill. The river had drawn a circle around us.

I thought of my parents. Their room was untouched. I opened the door slowly, half-expecting to find them there. Only silence. But a different silence than before—a silence that had survived.

III. The First Gestures

Outside, two children were playing with a ball near the house. Their laughter was the only sound besides the wind. Life, returning in small ways.

I grabbed a broom, a shovel, a bucket. I filled bags with rot from the fridge, carried them to the dump. Then I lit incense—oud, the same kind my mother used—and let the smoke drift through each room. It felt like a small ritual, a cleansing not just of odor but of absence.

As I swept the terrace, a voice called up. My neighbor — Ahmed, the one whose name I learned only during the evacuation — stood in the street below.

“You came back,” he said. Not a question.

“So did you,” I answered.

He nodded toward the lower streets. “They need hands down there. Tomorrow.”

I said I would be there.

We did not shake hands. We had shared the waiting. That was already enough.

IV. What the Mud Taught Me (Even from Dry Ground)

I had promised buckets and shovels in my last dispatch. I had imagined mud to my knees, walls to scrub, the weight of return made literal.

Instead, I found a house intact. A hill that held. A fridge that rotted, yes, but floors that were dry.

I felt, strangely, almost guilty. As if my resilience had been too easy. Too clean.

Then I walked down to the flooded neighborhoods. I saw the chest-high lines on other people’s walls. I touched their mud. And I understood: resilience is not measured by what you endure, but by what you do after.

My work was lighter. My responsibility was not.

I thought of the olive trees I had harvested weeks ago, the ones I called “silent historians.” Their roots had held. They had absorbed this excess and would keep growing. My city would too.

But resilience, I now understood, is not just philosophy. It is the weight of a bucket, the ache in your back, the decision to clean a room that smells of rot because it is your room.

Philosophy is clean. Mud is not.

V. Returning Is Not Reversing

I thought of my own philosophy — the “Olive Grove Economy” I had written about from Málaga. I had spoken of roots that survive droughts.

Now I had seen it: roots that survive floods. Not metaphorically. The olive trees I harvested weeks ago, their roots deep enough to hold when the water came.

Rooted Nomadism was never about staying still. It was about growing deep enough that you can leave, and return, and still be standing.

I am back in Ksar el Kebir. My house is intact. My city is healing.

But return is not reversal. The flood did not just take; it added. A layer of silt on the ground, a line on the wall, a memory in every stone. And for me, a deeper understanding: roots are not where you come from, but what you carry when you return.

The sardines will swim north with their messages. The olive trees will record this February in their rings. And I will write—not from waiting, but from the ground.

Still here. Still working.

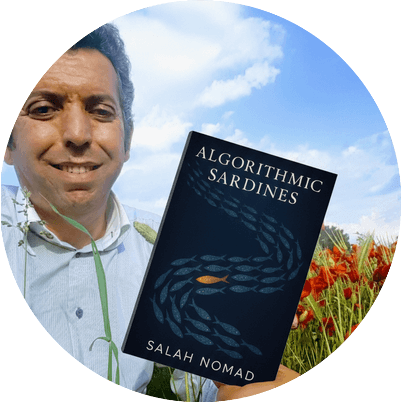

Salah Nomad

Ksar el Kebir, Morocco

February 16, 2026

This is the third and final part of “The Strait Remembers”, documenting the 2026 floods. Read the first dispatch “Water and Clay” from inside the evacuation, and the second “The Phantom City” from the waiting.

Subscribe to Rooted Nomadism for what comes after the mud — the rebuilding, the remembering, the return to rhythm.

Comments