Ksar el Kebir: The Phantom City That Still Breathes

February 9, 2026 | From Larache, Morocco

I. The Empty Streets That Are Not Empty

Today, Ksar el Kebir stands almost empty.

Not destroyed. Not erased. But suspended.

Its inhabitants have scattered into neighboring towns and regions — Larache, Tangier, small villages on higher ground. They wait in borrowed rooms, in relatives’ apartments, in temporary shelters. They wait for the sky to calm, for the soil to dry, for permission — from weather, from river, from authority — to return.

The city waits too.

Only the cats and the dogs remained.

Stray cats roam silent streets where markets once opened at dawn. Dogs wander between closed shops and mud-streaked walls. Images circulate — police officers and security forces bending down to feed them. Uniforms beside bowls of food. Authority kneeling before vulnerability.

In a strange way, these images say everything.

A city empty of people, yet not empty of care.

But not everyone could leave.

There are tragic cases — elderly individuals, sick residents, people whose bodies would not allow displacement. Police officers move door to door, knocking carefully, insisting, verifying. They check every house to make sure no one has been forgotten inside this temporary silence.

It feels like a scene from a film — wind moving through empty streets, cameras panning over balconies without voices.

Except this is not fiction.

II. When Infrastructure Becomes Tension

Ksar el Kebir does not usually appear in international headlines. It appears in memory — in trade routes, in olive harvests, in quiet provincial continuity.

But at the end of January 2026, water rewrote the introduction.

The dam upstream — the Oued El Makhazine — surpassed what numbers consider reasonable, rising beyond 140% of capacity, approaching thresholds that transform infrastructure from reassurance into tension.

Since September, the sky had been depositing its weight: between 600 and 845 millimeters of accumulated rain. When storage becomes saturation, calculation shifts from prevention to redistribution.

Water does not negotiate with percentages.

The Paradox of Protection

The dam did not fail. It performed its function.

Controlled releases were initiated to prevent rupture — a rupture that would have meant catastrophe beyond measure. Yet those necessary, rational releases intensified flooding downstream. In some sectors, waters rose to extreme levels, overtaking urban space by several meters.

This is the paradox of modern hydrology: To prevent collapse, one must redistribute impact.

The river was not angry. It was full.

And when a system exceeds its design, everything downstream becomes negotiation.

February 7–9: Holding Breath

The peak came between February 7 and 8.

Evacuations multiplied. Estimates spoke of tens of thousands — perhaps more — moving at once. On February 8, total confinement was declared.

Low-lying neighborhoods disappeared under brown silence. Roads dissolved into reflections. Shops shuttered. Ksar el Kebir — a city layered with Phoenician, Roman, and Andalusian memory — was described in the media as a “ghost town.”

But from within, it did not feel ghostly.

It felt paused.

On February 9, the alert remained at its highest level. Rescue operations continued. Sand barriers rose. Pumps hummed. Civil protection units moved through streets that no longer recognized their own geometry.

No casualties were officially reported — and that fact matters. Deeply.

Logistics saved bodies. But the city itself remained submerged in places, especially along the Loukkos’ edge.

III. Waiting Through Screens: The Digital Vigil

I never thought I would measure the state of my city through a vertical screen.

And yet, these past days, I have spent more time on social media than I care to admit — scrolling, refreshing, searching for fragments of Ksar el Kebir. For news about my neighborhood. About the street where my parents’ house stands. About the house itself.

I am not searching for headlines. I am searching for angles.

A corner of a wall. A balcony railing. The curve of a familiar sidewalk.

The official version exists, of course. Statements, press releases, structured updates. They speak of water levels, controlled releases, evacuation numbers, coordination efforts. They are necessary. They are measured.

But social media breathes differently.

It is raw, fragmented, emotional. It is an alternative layer of reality — unfiltered voices, shaky cameras, spontaneous commentary. It shows what statistics cannot hold: mud on stairs, cats on rooftops, neighbors calling each other by name.

Sometimes it contradicts the official tone. Sometimes it complements it. But always, it feels closer to the pulse.

I scroll not as a journalist. Not as a philosopher. But as a son.

And then I think of my plants.

The pots I left on the terrace — arranged carefully along the wall, some in clay containers, some in simple plastic. I used to water them at sunset when I was there.

Now I am not there.

And strangely, I realize: they will not lack water.

The same climate that displaced us — the persistent humidity, the daily rainfall — is watering them in my absence. The sky has taken over my task. What forced me to leave is also sustaining what I left behind.

There is something humbling in that.

We think we are the caretakers. Sometimes we are only temporary assistants.

IV. Messages Sent by Sardines: The Strait Remembers

I did not expect this second absence.

As if leaving Ksar el Kebir was not enough, another longing opened quietly inside me:

Málaga.

This year, I missed the Carnival of Málaga — the explosion of color and irony that transforms the city every February. The scent of fried anchovies mixing with perfume and sea salt. The laughter that refuses to take itself seriously.

I was not there.

While the streets filled with costumes and confetti, I was following from afar — from my birthplace, from the north of Morocco, from Larache.

From Lixus.

From the mouth of the Loukkos, where the river dissolves into Atlantic salt.

There is something poetic in this geography of longing: sending messages to Málaga from the very edge where fresh water meets ocean. Standing where currents begin their horizontal conversations.

And I speak into them.

I pass my messages north from Larache.

I entrust my thoughts to the sardines.

Yes — my messenger sardines again.

They swim through the Strait without borders, carrying invisible information in their silver bodies. I imagine they also carry whispers.

“Tell Málaga I am thinking of her,” I say silently. “Tell her I did not forget.”

Yesterday, I went to the central market of Larache.

The market was alive in that quiet way coastal markets are — fishermen unloading crates, scales flashing under fluorescent light. The smell of sea and metal and lemon.

I ordered grilled sardines — fresh from the Atlantic. Grilled sardines from Larache.

Charred skin, soft inside, eaten with bread and fingers. Simple. Honest.

But while I ate them, my body was in Larache and my soul was somewhere else.

My soul was in Málaga.

On the beach. Near the beach shacks where sardines are grilled on reeds, stuck in sand beside wooden boats filled with fire.

There is a difference.

Larache sardines carry the Atlantic directly. Málaga sardines carry Mediterranean light — softer, warmer, more theatrical.

One is river meeting ocean. The other is sea meeting city.

I tasted both at once.

One in my mouth. One in memory.

And that is what this February has become for me — a month of double presence.

Body in Morocco. Heart between two shores.

Ksar el Kebir flooded. Málaga celebrating.

One city suspended in mud. One city dancing in costume despite storms.

And I stand in between — at the edge of Lixus, ancient trading post where Phoenicians once exchanged goods between Africa and Iberia. Nothing has changed, really. The exchange continues.

Only now, what crosses the water are not amphorae of oil, but emotions.

I send longing north. I receive nostalgia south.

The Carnival continues without me. The smoke rises without my shadow among it. The streets echo with songs I can only watch through fragments on a screen.

But I do not feel divided.

I feel expanded.

Because to miss a place this deeply is proof of having belonged to it.

V. The City That Breathes Through Absence

From afar, Ksar el Kebir appears empty.

But it is not empty.

It is inhabited by waiting. By memory. By suspended return.

A phantom city is not one without life. It is one where life has stepped aside temporarily, trusting that it will come back.

And somewhere in those quiet streets, under grey sky and drying mud, the city still breathes — slowly, patiently — waiting for the footsteps of its people to return and complete the sentence.

140%. 600 millimeters. Five meters of water.

These numbers describe volume. They do not describe weight.

The weight of leaving a house. The weight of watching a river occupy streets you walked as a child. The weight of realizing that the Loukkos — patient, agricultural, generous — still remembers its ancient floodplain.

Ksar el Kebir has survived empires, invasions, transitions of language and flag. This flood will not erase it.

But it will mark it.

The dam exceeded capacity. The river exceeded boundaries. And perhaps we exceeded an illusion — the illusion that control means permanence.

Water has no memory. But we write memory in water.

And when it retreats, it leaves behind more than mud. It leaves recalibration.

Still here, still waiting,

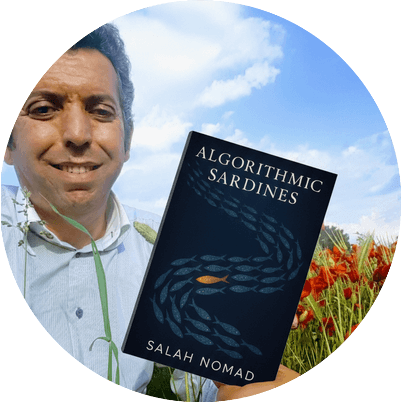

Salah Nomad

Larache, Morocco

February 9, 2026

This is the second article in the series “The Strait Remembers”, documenting the 2026 floods and their resonance across the Mediterranean. Read the first part, “Water and Clay”, written from inside the evacuation.

The third part, “Returning to the Mud,” will document the physical work of return — because resilience is not just philosophy, it is also buckets and shovels.

Subscribe to Rooted Nomadism for meditations on resilience, not just news.

Comments